by Birgitta Lemmel*

In 1865, soon after production at his very first company – Nitroglycerin Aktiebolaget, at Vinterviken outside Stockholm – had got started, Alfred Nobel left Sweden for Hamburg with the aim of creating a company for the production of blasting oil (the brand name for nitroglycerine) in Europe. He had been encouraged to set up business in Hamburg by the Swedish-born brothers Wilhelm and Theodor Winkler, sons of a Hamburg businessman who had been engaged in the import and export trade in Sweden.

The sons, who had taken over their father’s company Winkler & Co. in Hamburg, had earlier been impressed by Alfred Nobel’s demonstrations of the explosive power of nitroglycerine. Times were bad and trade with Sweden was becoming less profitable so the brothers were searching for a new product. They found what they were seeking in Alfred’s blasting oil.

Sign for Dynamit Actien Gesellschaft

On October 10, 1865, Alfred Nobel bought 42 hectares of land at Krümmel, an isolated hilly area very similar to the environment at Vinterviken. Krümmel was situated near the village of Geesthacht, about 30 kilometers from the center of Hamburg, on the shore of the river Elbe. The advantages of the site was that it was bordered by high sand dunes on one side, which would protect the neighboring village of Geesthacht in case of an explosion. On the other side was the Elbe, which offered good potential for transportation. Hamburg, with Europe’s largest port, was not far away.In June 1865, Alfred Nobel registered Alfred Nobel & Company (today Dynamit Actien Gesellschaft – Dynamit A/G), in Hamburg’s trade register. This was his first foreign company. The Winkler brothers and a lawyer named C. E. Bandmann became his first partners in this endeavor. A warehouse in Hamburg harbor was later set up as a provisional laboratory, while Alfred Nobel set out to examine the surrounding area, in order to find a suitable place for a factory. In this laboratory, he prepared a small quantity of blasting oil, which he brought to the mining districts, where he held demonstrations to show the superiority of blasting oil to other explosives. His demonstrations in places like Dortmund, Klausthal, and Königshütte were reported in the local papers.

The Krümmel factory in 1865.

The local authorities were familiar with the properties of nitroglycerine. One reason for their approval was Krümmel’s isolated location. Their permission, however, included numerous regulations and conditions. The buildings had to be separated from each other, and all buildings used for the production of blasting oil had to be sheltered by high embankments. Another condition was that the plant should be subjected to regular inspection.

The Krümmel factory in 1915.

The ground at Krümmel consisted largely of the sterile sand called kieselguhr that would prove crucial to Nobel’s blasting oil. Kieselguhr (diatomaceous earth), a form of hardened algae as fine as powder, proved to be the absorbent material he needed to turn the liquid nitroglycerine into a safer explosive.

From 1865 to 1873, Alfred Nobel had his very simple home and his private laboratory close to the factory in Krümmel and the company’s business offices in Hamburg. From here, the firm of Alfred Nobel & Co. dispatched nitroglycerine explosives in steadily rising quantities, not only to a large German market, but soon to other European and overseas markets as well.

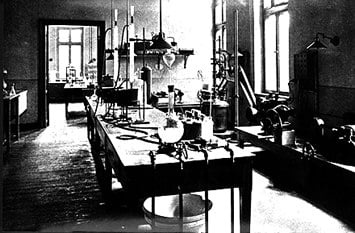

Laboratory at Krümmel in 1915.

The Krümmel works were demolished by explosions both in 1866 – before dynamite – and in 1870. Each time, they were rebuilt and greatly expanded. Although there was unemployment in the region, people were afraid of working in the factory. When the Krümmel factory started production of blasting oil on April 1, 1866, the total work force was about 50, many of them Swedes. Alfred Nobel’s foreman at Vinterviken, an engineer named T. H. Rathsman, and several other workers had come from Sweden to set up the plant.

Loading of explosives at Krümmel in 1915.

More pictures of Krümmel

The manager’s house in 1880. Alfred Nobel also stayed here during his visits.

View of the Nobel site and the river Elbe around 1880.

The Nobel site around 1905.

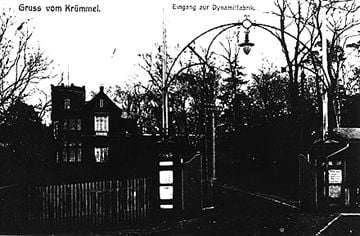

Entrance to the factory around 1908. The manager’s house is seen to the right.

Loading of powder at Krümmel in 1915.

After the first explosion on July 12, 1866, Alfred Nobel anchored a raft in the Elbe and set up a provisional laboratory on board. There he tried to improve the safety of nitroglycerine by mixing it with stabilizing inert materials such as charcoal, cement, sawdust etc. Finally, he also tried the sand from the Kümmel dunes – the kieselguhr – and here he found the perfect solution.

The mixture, a soft pliable material like dough, was patented under the name dynamite in 1867 and was shaped into rods suitable for insertion into drilling holes. Dynamite made it possible to revolutionize the transportation industry by greatly facilitating the construction of roads and railways, tunnels and canals. It has also played a crucial role in the modern mining industry.

Nitrator for the nitroglycerine factory at Krümmel, 1872.

Although nitroglycerine’s enormous explosive power was “tamed” and Alfred Nobel had an explosive that was almost safe to handle, production was still hazardous. The factory premises were primitive and the workers not cautious enough. On May 22, 1870, there was a second explosion, in which Rathsman and five others died.

Alfred continued to devote himself to the completion and improvement of his inventions, as well as the development of better methods of production. In 1875, he made his third important invention, which was patented in 1876 under the name of blasting gelatine – the blasting cap being his first, and dynamite his second. Blasting gelatine was followed later by Extra-Dynamite.

In 1873, Alfred Nobel moved his headquarters from Hamburg to Paris to be more in the center of events in his growing industrial empire. In 1875, the factory at Krümmel was the largest in the Nobel group of companies and was very profitable. When the number of Austrian and Hungarian customers increased substantially, after the construction of large factories at Zamky (near Prague) in 1868 and Pressburg (now Bratislava) in 1873, the company was given the name of “Deutsch-Österreich-Ungarische Dynamit A/G” (abbreviated “DAG”) in 1873.

Paul Barbe, a Frenchman who was based in the companies’ headquarters in Paris, was transferred to Hamburg, where he served as an efficient manager for a number of years. Alfred Nobel’s trusted friend Dr Gustav Aufschläger, became managing director in 1889, and served in this capacity for almost thirty years. Meanwhile, a separate company for Austria-Hungary was formed, A/G Dynamit Nobel, with headquarters in Vienna. In 1884, Deutsche Union (Interesse-Gemeinschaft IG) was formed from three companies. DAG Deutsche Sprengstoff A/G, Rheinische Dynamitfabrik and Dresdner Dynamitfabrik. In 1886, Nobel’s Explosives, Deutsche Union and A/G Dynamit Nobel in Vienna were merged to become Nobel-Dynamite Trust Company. After Alfred Nobel’s death in 1896, all his shareholdings in Nobel companies around the world were liquidated, providing the financial basis for the Nobel Prizes.

Statue in memory of Alfred Nobel at the dynamite factory in Krümmel – victory of technology over natural forces.

During the first decade of the 20th century Dynamit A/G, with its Krümmel factory of 600 workers and its three German subsidiary companies (Schlebusch, Saarwellingen, and Pungstadt), was the largest explosives concern on the European continent.

During World War I, urged on by the German Empire, Krümmel with its 2,700 workers became an active part of the hectic war production of high explosives of ballistite type along with all the accessories for ammunition. But the clauses of the Treaty of Versailles put an immediate stop to this, and the production curve for all explosives turned downward.

The factories were badly affected and the post-war years were gloomy, but capital and German energy were not lacking. It was a matter of finding peace-time products that could be manufactured by using the companies’ excellent technical resources, engineers and workers, undamaged machines and existing laboratories. Everyone in the Nobel concern was spurred on by the need to convert the factories to peace-time conditions. In addition to a large research laboratory, two new factories were built at Krümmel, one for artificial silk and one for Vistra, both textile fiber products based on low-nitrated cellulose. Many of the manufacturing details for these new types of goods, which later played such a vital part in the textile industry, were based on Alfred Nobel’s private pioneering research and ideas during the years 1893-1894 in the laboratory at San Remo, Italy.

Between the years 1918 and 1924, Dynamit A/G bought up the majority of shares in four big German corporations. Production shifted to explosives for civilian use and a number of other goods vital to industrial life. In time and through intensified research, the company’s products were improved in a spirit of progress worthy of Alfred Nobel.

View of the Krümmel factory around 1928.

The period of peace between 1929 and 1939 was also a time of prosperity for the concern, which now had 3,000 workers in the parent company. Then came World War II. For decades after Alfred Nobel’s death and the institution of the Peace Prize, the Krümmel factory which Alfred planned in 1865 for production in the cause of peaceful industry, became one of Germany’s biggest munitions factories with over 9,000 workers.

Oddly enough, the factory was spared destruction until the very end of the war. During an Allied daylight air raid, as late as April 1945, it was wiped out by over a thousand heavy bombs, whose explosive power was based on Alfred Nobel’s own inventions. A bronze bust of Alfred Nobel which was found among the ruins, damaged by bullets but nonetheless upright, was set up in the administration building. During the 1950s, the site was cleared of ruins and used for building the nuclear power plant of Krümmel.

The Krümmel factory’s pioneer days in the 1860s have left traces in the neighboring town of Geesthacht. Typical Swedish surnames such as Bengtsson, Pettersson, Johansson and Svensson, borne by the third or fourth generation descendants of the workers who went to settle there with Nobel, remind us of how it all began more than a hundred years ago.

Photos were kindly provided by William Boehart, Museum und Archiv Krügersches Haus, Geesthacht, Germany.

* Birgitta Lemmel was Head of Information of the Nobel Foundation in 1986-1996.

First published 28 February 1998